f1 f1.4 f2 f2.8 f4 f5.6 f8 f11 f16 f22 f32 f64

All cameras, whether an ancient film camera, or a more modern digital, work in pretty much the same way. Photographs are taken by letting light fall onto a light-sensitive medium, which records the image.

The aperture controls the amount of light that reaches a light sensitive medium, wither it be digitally, film, or paper. The aperture controls the intensity at which light will strike the film. An aperture acts much like the pupil of an eye that opens larger as light decreases to let in more available light. The pupil shrinks when light increases to reduce the amount of light entering the eye.

Put simply, a camera consists of a light-tight box or even film canister, that stores a light-sensitive device, a lens that magnifies and focuses the image onto that light-sensitive device through a hole in the box (called the aperture), and a shutter that opens and closes when you press the shutter release, exposing the film to the light; this is why a picture is sometimes called an exposure.

The amount of light entering the camera depends on the amount of light in the scenes that you’re photographing. A bright sunny cloudless day has more available light than a cloudy one, which in turn has more light than an indoor scene lit by tungsten lighting. To make the picture look right, we have to expose the film to the right amount of light. Too short, and the image will be light, or underexposed. Too long, and the image will be dark, or overexposed.

The combination of aperture and shutter speed are related, and effect the exposure value. The faster the shutter speed, the larger the opening of the lens and visa versa. Aperture and shutter speed have to come together in balance based on a given lighting scenario to make the proper exposure.

The diameter of an aperture is measured in f-stops. A lower f-stop number opens the aperture and admits more light onto the camera. Higher f-stop numbers make the camera's aperture smaller so less light hits the film.

When an aperture is opened up by one f- stop, the amount of light which reaches the film is doubled.

Aperture settings can be used creatively to control depth of field, how much of a photo is sharp in front and back of where you focus on the main subject. The technique is useful for close-up and portrait shots.

Shutter speed

B 1 2 4 8 15 30 60 125 250 500 1000 2000 4000

The concept of shutter speed isn’t too hard to understand. The longer you leave the shutter open, the more light that strikes the film, resulting in a darker image.

Shutter speeds are measured in fractions of a second, and is the time taken from when the shutter opens to when the shutter closes, after you’ve press the shutter. Moving from one speed to the next either halves the amount of light that can enter the camera or doubles it. The change from one speed to another (and halving or doubling the light that enters the camera) is called moving a stop. What affect does changing shutter speed have on your final image? As well as controlling the amount of light that enters the camera, shutter speed effects motion and blur. While fast shutter speeds can “freeze” motion, slower shutter speeds extend activity or blur moving objects.

EXAMPLES:

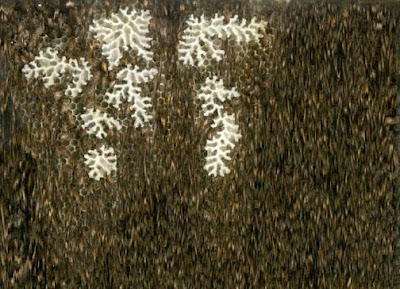

Lots of bees - Slow shutter speed - Large aperture -

Lots of bees - Slow shutter speed - Large aperture -Shallow depth of field

Not so many bees - Slow shutter speed- Blurry queen

Not so many bees - Slow shutter speed- Blurry queen Wingless queen - Fast Shutter speed - Stopping action of the waggle dance

Wingless queen - Fast Shutter speed - Stopping action of the waggle dance One blurry bee - Slow shutter speed

One blurry bee - Slow shutter speed Sharp bee - Fast shutter speed

Sharp bee - Fast shutter speed Large bee - Small aperture -Plenty depth of field

Large bee - Small aperture -Plenty depth of field Small bee - Large aperture - Shallow depth of field

Small bee - Large aperture - Shallow depth of field Don't play with bees in traffic - Long exposure - Bad idea

Don't play with bees in traffic - Long exposure - Bad idea

No comments:

Post a Comment